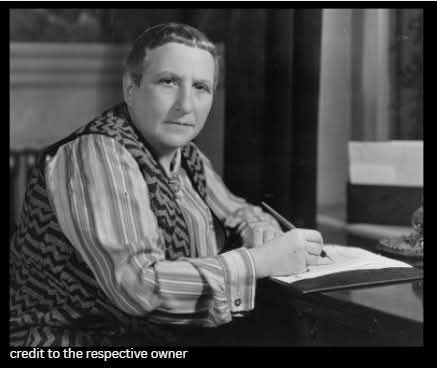

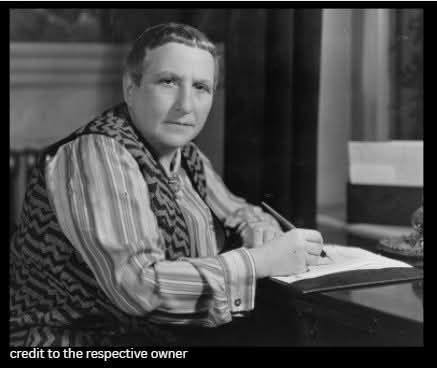

She called herself a genius—and for once, the world didn’t argue. Gertrude Stein was more than a writer. She was a force of nature. In her Paris salon, beneath the glow of oil lamps and the haze of cigarette smoke, some of the 20th century’s most influential artists and writers gathered to drink, argue, read, and be seen. She didn’t just host them—she shaped them. Picasso, Matisse, Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, and many others passed through her doors and left transformed. If they were raw talent, she was the whetstone.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1874 and raised across America and Europe, Stein arrived in Paris in her early thirties with her brother Leo, a sharp eye for art, and a bold disregard for tradition. While Leo collected canvases, Gertrude collected minds. Her home on Rue de Fleurus became the unofficial headquarters of the modernist revolution.

But Stein didn’t just influence great men—she lived openly and unapologetically with her partner, Alice B. Toklas, at a time when most queer women were erased or forced underground. Their partnership was quiet but unshakable. Toklas typed Stein’s manuscripts, managed their home, and became her most trusted critic. Gertrude called her “my wife,” and wrote an entire memoir—The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas—as a tribute to their life together, cleverly telling her own story through Alice’s voice.

Her writing wasn’t always easy. Dense, repetitive, strange—some found it frustrating, others revolutionary. But Gertrude didn’t write for approval. She wrote to experiment, to deconstruct, to challenge language itself. In doing so, she laid the groundwork for generations of writers, especially women, to claim their intellectual space.

During the war, she stayed in France—even under Nazi occupation. That part of her life remains complicated. She translated speeches by Marshal Pétain, the leader of the Vichy regime, and questions about her political loyalties still linger. But like everything about Stein, the story is complex. She was a woman of contradictions: Jewish, yet protected by collaborators; a radical literary voice, yet sometimes conservative in politics.

Gertrude Stein was never meant to be easily understood. She was brilliant, blunt, funny, opinionated, and impossible to ignore. She made her salon a battleground for ideas and turned her life into art. She didn’t just witness a cultural revolution—she sparked it.