The birds knew first. Then the earth opened up and swallowed an entire town alive.

October 9, 1963. A quiet evening in the Italian Alps. Twelve-year-old Micaela Colletti was getting ready for bed in the mountain town of Longar one when she heard something strange—thousands of birds crying out in unison, their voices urgent and afraid.

Then came the sound. Not thunder. Not an earthquake. Something worse.

Her grandmother later described it as “millions of metal doors slamming shut at once.” The roar grew so loud it drowned out thought itself. Her grandmother rushed to close the shutters, whispering words that would prove terrifyingly inadequate: “A storm is coming.”

What came wasn’t a storm. It was the end of the world.

In seconds, the ground disappeared beneath their feet. The entire town transformed into a churning river of mud, stone, and destruction. Three-story buildings collapsed like cardboard. Roofs tore away and flew through the air like leaves. Cars tumbled end over end, becoming desperate rafts for families trying to escape the impossible.

Micaela was swept 350 meters by a wall of water and debris. Buried under mud. Certain to die.

She survived. Barely. One of the fortunate few.

Nearly 2,000 of her neighbors did not.

The monster that destroyed Longarone wasn’t born from nature—it was built by human hands. And the worst part? Everyone saw it coming.

The Vajont Dam stood 262 meters tall in a narrow alpine valley, the tallest dam in the world. Built in the 1950s to generate hydroelectric power, it was hailed as an engineering marvel, a symbol of Italy’s postwar ambition and progress. But from the beginning, there were warnings.

The valley walls were unstable. Landslides had already occurred during construction. Geologists raised alarms. Local residents reported cracks appearing in the mountainside. The reservoir water level was causing the slopes to shift.

But there was money to be made. Political reputations to protect. Energy to generate. The warnings were dismissed, downplayed, ignored.

On the night of October 9th, nature delivered its verdict.

260 million cubic meters of mountain—an entire hillside—broke free and plunged into the reservoir at over 100 kilometers per hour. The impact created a wave more than 100 meters high that surged over the top of the dam and down the valley below.

The dam itself didn’t break. It held firm, a testament to its engineering. But that was irrelevant to the people of Longarone.

The wave hit the town at nearly 70 kilometers per hour. In less than four minutes, Longarone and three nearby villages simply ceased to exist. The water scoured the valley floor down to bedrock. When it was over, 1,450 of Longarone’s 1,500 residents were dead.

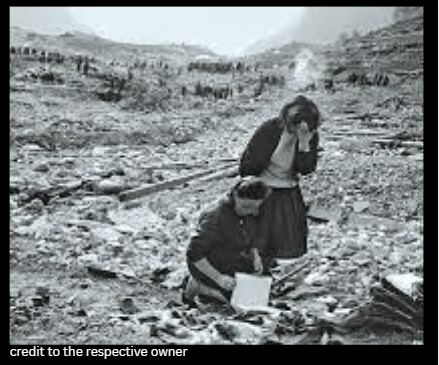

Micaela’s grandmother didn’t survive. Neither did most of her friends, teachers, or neighbors. An entire generation—gone in the time it takes to boil water.

The tragedy of Vajont wasn’t a natural disaster. It was a man-made catastrophe born from arrogance, negligence, and the deadly calculation that profit mattered more than precaution.

Today, the Vajont Dam still stands in that quiet Italian valley. The reservoir is empty now, drained and abandoned. The dam serves no purpose except to remind us what happens when ambition ignores wisdom, when economic pressure silences scientific warning, when those in power decide that some risks are acceptable—as long as someone else pays the price.

Walk through that valley today and you’ll find memorials, flowers, photographs of faces that never grew old. And above it all, that massive concrete wall—perfectly intact, technically flawless, and utterly damned.

Some monuments celebrate human achievement. Others stand as warnings carved in stone and grief.

The Vajont Dam is both. And neither.

It’s a gravestone for nearly 2,000 people who died because someone decided their concerns weren’t worth listening to.

The birds knew first. They tried to warn us.

We should have listened.